EMR adoption can cause tension in healthcare organizations.

80 of Central Maine Healthcare’s 300 physicians were alleged to have left this year due to discontent with an EMR, for example. Many studies have also linked EMR use to increased physician burnout. The late Pulitzer-prize-winning journalist Charles Krauthammer even called the EMR “healthcare’s Solyndra”.

There are many sources for the tension EMR adoption appears to cause. We’ve addressed some of them before. In this article, we’re focusing on one of the most important: the challenge of process integration.

At its simplest, process integration asks if the organization’s workflow is a match for the EMR’s. Can the EMR be incorporated into the practice’s way of doing things? Can the practice’s existing processes be made to fit into or work with the one built into the EMR?

This is critical in deciding how people respond to an EMR. When a mismatch happens, tension arises. In fact, reviewing the different studies of doctors complaining about EMRs, this is the chief source of trouble: “It’s not the way we do things.”

Of course, not all change coming from EMR adoption is viewed negatively by healthcare professionals. Consider the following passage from a study of how EMR/EHR usage affects physicians’ decisions to continue practicing at their hospitals:

Results suggest that when EHRs create benefits for doctors, such as reducing their workloads or preventing costly errors, their duration of practice increases significantly. However, when technologies force doctors to change their routines, there is an obvious exodus, though it’s more pronounced with older doctors, especially specialists, and those who have been disrupted in the past by IT implementations.

So changes can be tolerated if they are mitigated by a benefit. In some ways, those changes might act more like facilitators. On the other hand, the changes that bring no benefits are viewed as disruptions (which admittedly brings to mind Christensen’s seminal theory of Disruptive Innovation—a suggestive association!).

What Is Disruptive About EMRs?

The best way to answer this question is to look at the users’ complaints. These tend to differ because preferences and EMRs vary. There are some commonly-brought-up remarks, though. Consider the responses to our survey of Philippine doctors who have already tried EMRs. Some of the most commonly-given complaints have been represented in the quotes below:

“I used a local software that was being promoted in PGH. I tried it, started to use it but there were no updates and it was inconvenient to use. I sent my feedback and they never responded.” – Oncologist from Baguio

“I used an EMR from a US software company. It’s fine, but it’s not tailored for local and it has been in beta for years. Not many big improvements over the past years.” – Ophthalmologist from Taguig

“I came from an Australian-based app company. It fit my needs with managing the schedules and patients but the notes were limited. I used them for a year but switched because it was obvious that they were not going to add anything specific for doctors.” – Obgyne from Makati

Other common complaints include the following:

- Cluttered interfaces

- Non-user-friendly design

- Lack of simultaneous access (for physicians and their nurses)

- Excessive alerts (some EMRs don’t let users filter their messages/alerts, which leads to added work when the application sends the user hundreds of messages that he must wade through just to find a few important alerts)

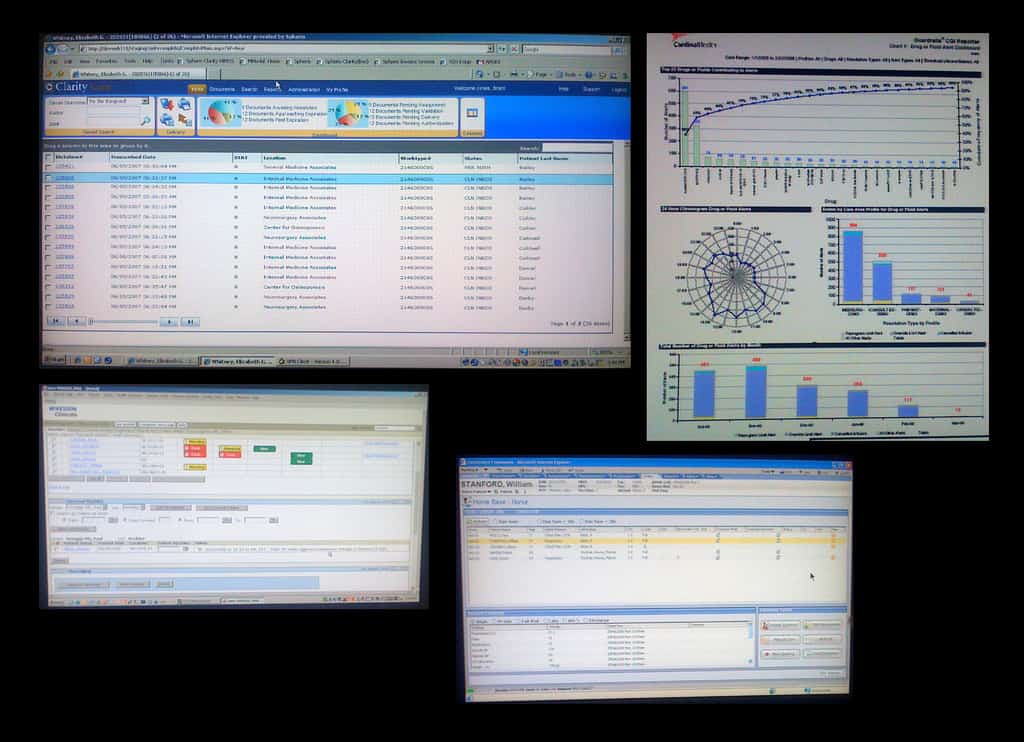

This screenshot of cluttered EMR interfaces was taken by Juhan Sonin, an aesthetic designer and Creative Director of Involution Studios. Sonin had been inspecting EHR booths at the HIMSS Conference ’08 and described most of the programs’ usability and design as “horrid” at the time. Doctors are still saying the same of most EMRs today. Image license here.

All of these indicate a process issue. Just think about it:

An EMR is inconvenient to use when it gets in the way of the user’s routine.

It’s inapt when it isn’t designed to meet the more specific (sometimes location-sensitive) needs of its users.

It’s a hindrance when it doesn’t let users take the notes they need or permit staff access as required.

In other words, the problem is that there’s no synergy between the process preferred by the EMR and that preferred by the users.

Who Should Make Changes?

So what should you do when the organization endorses one method of doing things and the technology endorses another?

Generally speaking, it would be wiser for the technology to adapt. Adjusting tech is usually easier than forcing change on organizations (and the people in them). Besides, there’s also the matter of who’s in charge when determining the way an organization should work.

If you make the organization adapt to suit the tech, that essentially gives outsiders (the tech developers) the final say on the topic. That doesn’t make sense when they don’t actually work in healthcare: they’re typically programmers, not physicians/nurses. They lack the sustained, in-the-trenches experience necessary to make determinations like that.

Outsiders like businessmen and developers can have useful insights for a hospital’s staff, but they shouldn’t run the show.

Some developers work with physicians when creating their programs, of course. We certainly did, and other serious EMR providers have done the same. But there are problems that can crop up even then.

- The resulting EMR may be geared too specifically towards a particular organization’s way of doing things. This goes back to the fact that different doctors/teams have different processes. If the EMR developers tailor their program too closely to just a small number of doctors’ (the ones they work with) preferences, they may end up alienating other users with the end product.

- The physicians chosen for feedback and consultation may not be representative of the EMR developer’s target market. What if they happen to use processes that are wildly divergent from the ones used by most other doctors in the target market, for example? Again you get a product that doesn’t cater to its target users’ needs.

- The developers’ feedback loop may not be conducive to actual improvements in the development process.

These are just a few of the possibilities. Even if all of these could be overcome, there remains a deeper issue. After all, there’s a critical assumption we’re making here: that the processes employed by the end-users are actually ideal.

But “ideal” isn’t a reality we face often.

Current Healthcare Processes Could Be a Problem Too

A recent article from the Harvard Business Review raised this point. Writers John Toussaint, MD and Kathryn Correia noted that there may be an inherent problem in the US healthcare system’s processes. Many of them are technically under-efficient, non-standardized, and of questionable efficacy.

According to the article, the processes tend to be individual-dependent, not system-dependent:

The hard part is to get the doctors, nurses, and administrators to agree on what is the best way to deliver the care. Since the doctors control most care decisions, the rest of the provider team follows the doctors’ lead. If the doctor wants to do things a certain way, that’s what is done. The problem is the next doctor wants it his way and so on. Eventually, we end up with a hopeless mess in which no one knows how anything should be done on any given day. And good luck to a new nurse or technician coming into the system who must learn a multitude of work processes and remember the doctor-dependent differences.

If this is true, it would show even more often in large organizations than in small, independent practices. That’s because there are more physicians involved in the former.

This is definitely the case as well for other countries, including the Philippines.

How We’re Dealing with Process Integration in the Philippines

I could continue to go on and cite different references or I could just talk about how we are dealing with EMR process integration.

Like what I mentioned at the start, process integration mainly asks if the organization’s workflow is a match for the EMR’s.

Does the workflow FIT with what the EMR can offer or can the EMR be adjusted enough to FIT the existing workflow? To cap it off, it needs to have a clear benefit for the users.

As long as there’s enough visible benefits, physicians will tolerate, forgive and work with the software but at the same time, there needs to be trust that the software vendor will continue to improve and make the physicians’ life easier in the long run.

It’s a fine balance and both sides will have to work together.

One of our goals for the past years with SeriousMD was to better understand the needs of the Filipino physician. To understand the different workflows and to build that trust by showing that we are improving and that we continue to innovate.

It’s not perfect. We’re not perfect, but it’s good enough. We’re still improving and we continue to do so each and every day.

SeriousMD at this point can be plugged into almost any workflow and be configured to adapt to different needs, locations and use-cases.

At the end of the day, our users from all around the country are our testament. They come from all sorts of fields, backgrounds and practice types. They all have their own workflows, forms and more. We’ve learned and we’ve made sure to hone SeriousMD to be able to adapt to their different needs.

[metaslider id=1990]