On the 19th of February, an expecting couple sought admission to one of the country’s foremost medical institutions. The unfortunate events that followed have been generally regarded the catalyst for a trend we now call “doctor-shaming”.

Doctor-shaming—what does it mean? Essentially, it is to humiliate a member of the medical profession before others. The shame presumably comes from airing something negative about or perpetrated by them.

Doctor-shaming can be done in personal, face-to-face conversations, technically speaking. However, when people speak of it these days, they usually refer to something that involves a larger audience. More specifically, they mean something that takes place on online channels or social media.

We need not stray far to see an example. The case that arguably sparked this fire—that of the expecting couple we mentioned earlier—is sufficient.

The Pelayo-UST Incident

At 3AM on a Friday, Andrew and Siarra Pelayo presented themselves at the University of Santo Tomas Hospital. According to the couple, they chose it because Mrs. Pelayo had also been getting her regular checkups there since November 2015.

The resident who saw them, Dr. Ana Liezel Sahagun, offered a contrary opinion. Upon inspection of the patient, Dr. Sahagun pronounced the case non-emergent and said it was also wiser for the couple’s finances if they transferred to a government hospital.

The Pelayo Family – screengrab from Dr. Willie Ong’s video

Mr. Pelayo had brought only 6,000 pesos with him that night. The doctor noted an admittance fee of 20,000 for the hospital’s cash-basis patients. She then recommended that the couple try one of two (more affordable) public hospitals in the area: the Jose Reyes Hospital and the East Avenue Medical Center.

Mr. Pelayo hailed a cab and transferred to the first of the recommended hospitals. However, he discovered that they had no available incubators, which prompted him to return with Mrs. Pelayo to USTH.

There, Dr. Sahagun again urged the couple to transfer to East Avenue Medical Center instead, saying there was still time. The Pelayos felt otherwise, asking her to reconsider. After insistence from both parties, the Pelayos decided on transferring again.

At the East Avenue Medical Center, Mrs. Pelayo was rushed to an operating room after she informed the physicians on call about her medical history (she had prior birthing issues). Upon inspection, the doctors were no longer able to detect a fetal heartbeat.

At 5:45AM, the doctors operated but could not save the baby. They also informed Mr. Pelayo later that the baby had perished because the operation had not been on time and that his wife could have been lost too.

Soon after, Mr. Pelayo posted an account of the experience on Facebook:

Mr. Pelayo’s final words in the post are translated below (broken up into paragraphs for clarity):

My deepest gratitude goes first to God for having saved my wife. Second, to the doctor who immediately took care of us [at the East Avenue Hospital] without mentioning or demanding money, who’s why my wife is still alive. Lastly, to the taxi driver who rushed to bring us to East Avenue Hospital so that they could help my wife and child.

To Dr. Ana Liezel Sahagun and her two colleagues, I wouldn’t have lost my son had you put saving the lives of my wife and child first. You’re merciless, putting MONEY before the lives of those you’re supposed to save.

Money can be found and worked for but A LIFE can’t be brought back. Can your consciences handle what happened to my wife, much less my child who fought to his last breath? To think my trust in you and UST Hospital had been so great, but what you did denied my child the right to live and to be with me.

The post was deleted later, but in the few days it was up, it was shared more than 140,000 times. The news media jumped on it and even more people took notice. Dr. Willie Ong released a personal interview with the Pelayos.

The Pelayo story prompted a strong public response, especially against Dr. Sahagun and USTH. Soon after it was published, the hacker’s group Global Security Alliance defaced the USTH website.

BREAKING: The UST Hospital’s official website was hacked by Global Security Hackers, a 19-member group. pic.twitter.com/FnjPsyJsAV

— The Varsitarian (@varsitarianust) February 28, 2016

The viral post had seemingly opened the proverbial can of worms. Other patients with similar experiences were all at once going online, venting both disappointment and vitriol.

Shields Thrown Up, Open Fire

The initial responses to the Pelayos’ experience were focused on sympathy and condolence. As more experiences like theirs came to light, however, people began to note a trend of patient complaint about doctors on public channels—of doctor-shaming on social media, to be precise.

Responses from “the other side” began to show more prominently now. These had already been present from the beginning, when physicians had come to Dr. Sahagun’s defense.

Dr. Mylene Basco-Tiamson noted, for instance, that Dr. Sahagun was still only a resident-in-training at USTH and had no ability to alter the processes of the hospital herself. Other doctors pointed to the firmness of hospital protocol.

Several also emphasized Sahagun’s professional opinion that, at the time she had inspected the patient, she believed the case had been non-emergent. The latter is an important point because of Republic Act No. 6615. This mandates that all hospitals (whether public or private) must render immediate medical assistance to emergent cases regardless of expense.

As the discussion moved beyond the Pelayo Case and onto public criticism of doctors in general, the opinions began to get even stronger. A Reddit post from a self-identified Filipino doctor touched off yet another commenting furor:

To doctors of reddit. I’m a filipino doctor, and recently, people have been doctor shaming a lot of doctors on social media. I hate filipino patients

So i’m a doctor, i’ve been working in a governement hospital for more than 5 years now and during that small amount of time, i’ve noticed a drastic change is patients attitude towards the doctors and all medical professionals ever since doctor shaming on facebook became a thing, in the recent months, people are posting more and more stupid stuff on facebook or any kind of social media how doctors are only after the money and that they should do this and not that and i’ve seen a lot of young doctors who havent started their careers yet get their name tainted by stupid people who post the doctors’ faces on facebook and say bad things to them. I am now thinking of giving up on becoming a doctor and just start a business or something or maybe just go abroad. Becoming a doctor in the philippines is not worth it.

So i heard this post went viral on facebook. I have to admit this experience has been very therapeutic for me. I suggest this to fellow doctors, annoy the hell out of other people be petty and angry and sarcastic. Just be sure to do it anonymously.

To those people who gave encouraging words and advices, thank you from the bottom of my heart

To those people who doesn’t have other things to do than butt in other people’s business online and irl because they think that their opinions matter, you can suck my d**k [our censorship, not the author’s]

Some physicians still posted more measured responses, however. Dr. Ron Baticulon wrote in his piece on the topic, for example, that

[i]t should be pointed out that the root cause of these online grievances is our inadequate health system, particularly in the public sector. […] The truth is, the concerns are mostly valid, although the demands not always realistic in government hospitals that are short of health care workers and run with limited resources.

Baticulon further wrote that doctor-shaming as a trend should stop nonetheless, not least because he was doubtful that it had ever reached “a positive resolution”.

Dr. Gia Sison wrote along similar lines:

Let’s face it doctors have earned their own place in society but this needs to be balanced with the humility of non-self-entitlement also. […] I must admit that the healthcare system plays a part but in lieu of the upcoming changes it will take, I think it’s high time that we as doctors begin to be open to feedback and vice versa. We are, after all, humans too and this is where we need your help, let us know how you feel but not to the point of shaming.

And still more doctors took to social media to weigh in on the issue:

@seriousmd shaming on social media should be shunned. There is always a better way to express thoughts and opinions w shaming people.

— Helen Madamba (@helenvmadamba) September 17, 2016

Critique for Caregivers: Blasphemy or Necessity?

Complaints about doctors are not new. They do seem to be on the rise, though. 2013 numbers from the UK indicated a steady increase of 67% in the number of patient complaints about physicians from 2007. In nearly the same period (2007-2011), Denmark saw an even greater increase of 88%. Ireland’s Health Service Executive reported a similar uptick recently.

Of course, these were formally lodged complaints as opposed to unregulated critiques on social media. Yet they still hint at a rising willingness or capability in patients to criticize their doctors for failing to meet expectations.

Whether this signifies rising patient expectations, lowered doctor efficacy, more accessible complaint channels, or even something else is up for debate. But it does suggest that the trend of patient complaint about physicians is not restricted to the Philippines.

Nor should it be, some would say. Part of the difficulty with the matter, especially the one brought to a head by the Pelayo Case, has been a muddling of issues. At times, the query has been “Should doctors be shamed on social media?” At others, it was “Can/should doctors be criticized” instead.

These are two (some might even say three) very different questions. In fact, while the former draws negatives from most in the healthcare industry, the latter actually draws affirmatives too… and for good reason.

Unpleasant though it may be, critique is often a guide for improvement. The UK’s Francis Report provides an example. A hospital under study, the Mid-Staffordshire NHS Hospital, had suffered 1,200 unnecessary deaths over 3 years. The report found that submitted patient complaints in that period had actually identified hospital issues that related to those deaths.

The former Mid-Staffordshire NHS Hospital, photo by Alistair Rose

Patients and their families supply potentially valuable perspectives that can identify weaknesses not easily seen from within the system. If codified, processed, and acted on appropriately, their feedback (critical though it may be) could even aid healthcare professionals.

So it might be suggested that hospitals and doctors can and should be criticized by their patients on certain occasions, if only so they know how to better the care they provide.

But now the question: when a doctor is shamed, does that achieve the same outcome?

The Perils of Reflected Damage

Like everyone else, doctors can and do suffer emotional ailments. They even have some of the highest depression rates by profession. Added stressors like doctor-shaming may make matters worse.

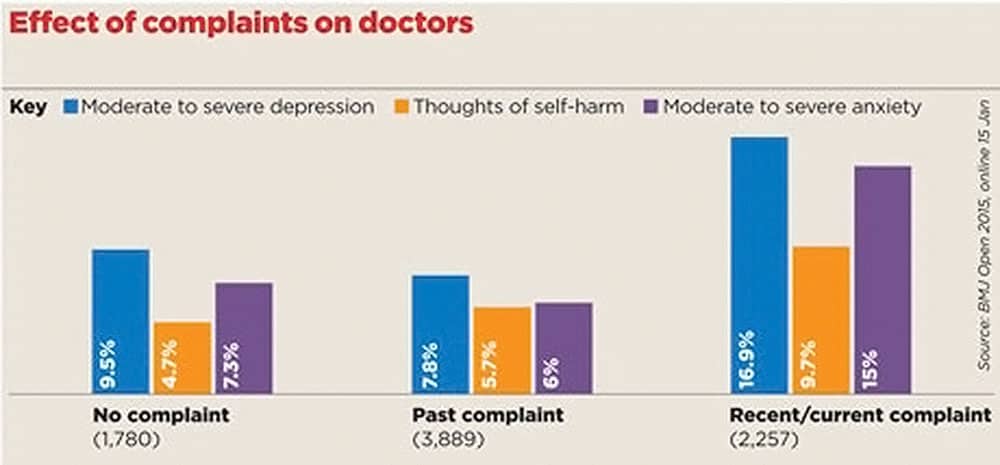

An Imperial College London study published this year affirmed the negative psychological impact of complaints on physicians. Consider that the ones in the study were already formally-filed complaints. Though serious, these were still relatively isolated in their social effects. Many formal complaints are handled with a measure of privacy that helps to protect the doctor from public vilification.

The same cannot be said for complaints aired through social media.

But the potentially noxious nature of doctor-shaming goes beyond the emotional harm it does the physician concerned. The greater problem for everyone may lie in the reflective character of its damage.

The Imperial College London study showed marked emotional injury in doctors after complaints.

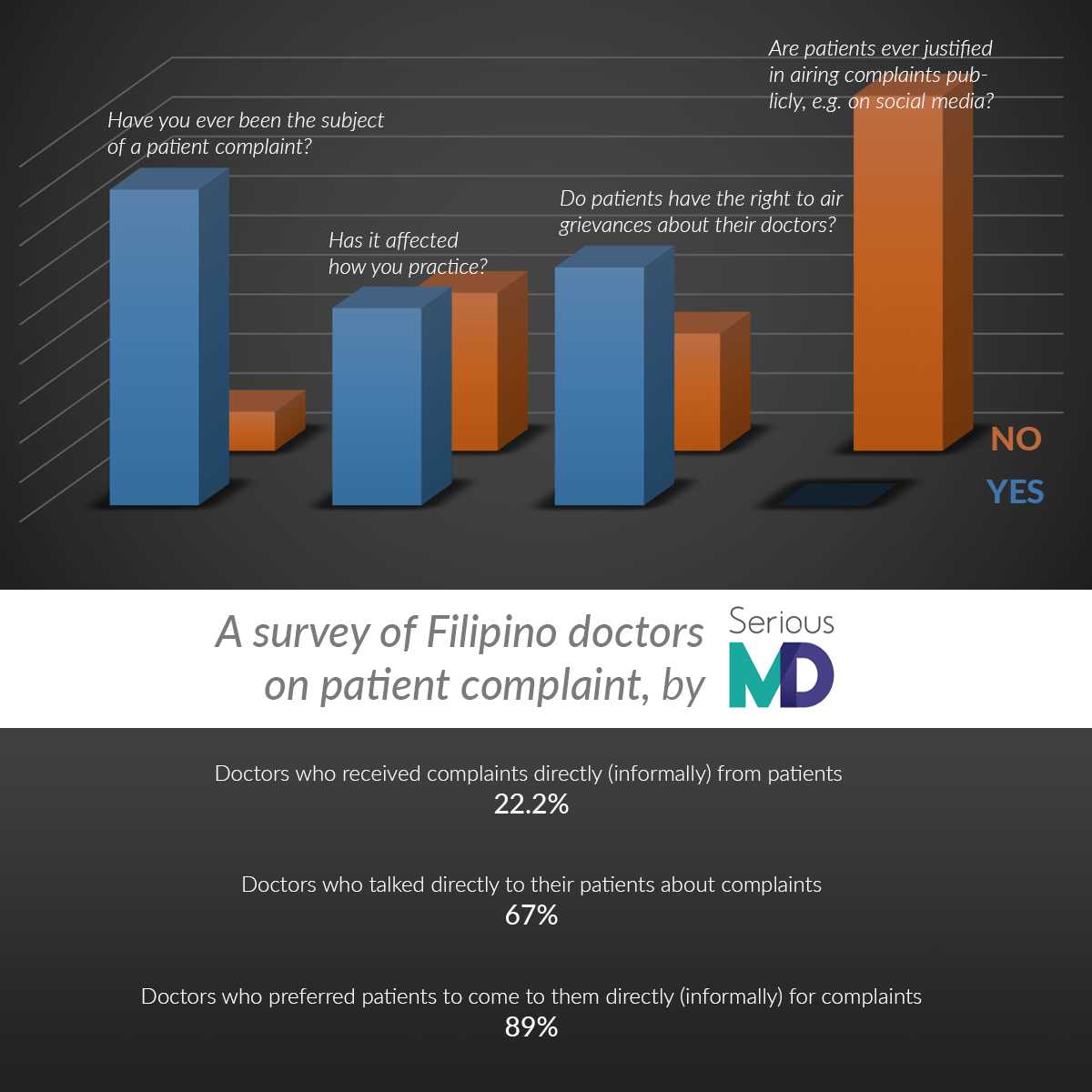

An example of the potent emotional response doctor-shaming can elicit from physicians is the anonymous Reddit post mentioned earlier in this article. Our own survey showed something like it. Asked to rate their feelings about patients airing grievances on public channels like social media, all respondents gave an answer of 1—the lowest (most negative) possible value.

When feelings run this strong, it is understandable that it should ripple into a physician’s professional life. 44% of respondents to our survey admitted to changing the way they serve patients after being subject to patient complaints. Of these, 50% admitted to the change being for the worse.

One respondent even specified this: “I don’t trust patients now.”

Trust is a vital part of the doctor-patient relationship, so this is significant. Sadness, depression, insecurity, disappointment—all of these have the potential to lower a professional’s efficacy at his job.

Most studies indicate considerable potential for adverse patient care to result from complaints about doctors. This is particularly when the circumstances of the complaint are deeply traumatizing to the physician.

Being shamed on social media, where virtually everyone can watch or participate, would qualify for most people—physicians or not.

Methods of Complaint and Money Matters

As noted earlier, critique is not the issue: all professionals must face it at one point. Rather, the concern seems to be the way critique is expressed. Doctor-shaming introduces added levels of psychological harm that might interfere with the goal of improving healthcare or the doctors who supply it.

At least one solution would appear to be promoting alternative avenues of critique for patients—either the formal (e.g. filing official complaints at hospitals) or the informal (e.g. approaching doctors directly).

Unfortunately, there are obstacles even here. For one thing, doctors actually avoid at least one of these avenues of complaint too.

Our survey found that most physicians prefer to be approached directly by the patient. Only 11% of respondents preferred to receive formal patient complaints. The rest were for a direct, more private approach by the patient. However, only 22.2% also claimed to have received complaints directly from their patients.

That doctors should shy away from the formal complaint channels is natural to some extent. There is worrying data from other countries showing that most doctors are unhappy with formal complaint processing procedures by and large, but such an opinion is hard to separate from the circumstance of a complaint’s existence in the first place.

That patients should also shy away from these channels—ones more concerned with checking doctors’ errors than theirs—might be more interesting. It could be part of the puzzle helping explain why doctor-shaming has taken off so readily in the country.

There are socioeconomic tensions at work here. This aspect might be suggested as a factor in patients’ hesitation to use the above-recommended avenues of complaint—and consequently, their willingness to use social media for it instead.

Unfortunately, there is yet a dearth of data here. However, there are prior related studies overseas that may help. For instance, a New York State study in 1993 already came to the conclusion that those on the lower end of the socioeconomic spectrum were less likely to sue for medical malpractice.

Another study from New Zealand indicated a decreased propensity for formal complaint in patients who lived in disadvantaged areas… or, curiously, who were of Pacific ethnicity.

Yet another from Taiwan found that patients living in urban areas were likelier to file formal complaints, noting that those from rural (and often less well-off) locations “may be unaware of the complaints process”.

It does not seem unreasonable to suggest, in light of these, that a fair number of socioeconomically disadvantaged Filipinos are either of two things:

- unaware of how to use formal complaint channels or

- unwilling to make use of them.

It may be a question of discomfort or disbelief in a system they consider foreign to their positions. When this is the case, it is more understandable that patients in this bracket can prefer informal complaint methods. Doctor-shaming methods via social media might appear nearer a judgement of the people—and this is a powerful idea in a country that has had several EDSA movements. It would not be out of the question to say that some may believe they have no other (valid) option for redress.

This in no way posits that formal avenues of patient complaint are futile. Medical regulatory boards, specific complaint-filing procedures, even medical malpractice litigation processes—all of these things are indispensable, whether doctors like it or not. They represent internal safeguards and monitoring tools in a system.

However, it may be suggested that the current procedures of formal complaint could be improved. If so many doctors seem to have issues with them and patients find them generally unfathomable or inaccessible, something needs to be done.

Communicating Expectations

Until reforms can be developed and implemented, the informal, direct-approach method seems the most palatable complaint channel to both parties for now.

The problem is, even this seems to be getting short thrift these days. Many patients are turning to social media and doctor-shaming instead—which brings us back to where we began.

Before anything else, it must be said that this tendency towards social media reportage of complaints could be reflective of socioeconomic and cultural issues at work again. Where patients distrust the mechanisms put in place for their protection, it is possible for them to feel similarly about the doctors themselves.

Doctors are part of a specialist class or profession. This sort of distinction as well as other (financial, educational) circumstances could ally them to the “upper-class” or “other side” in many patients’ minds.

In sum, the socioeconomic lines that render formal complaint channels inaccessible or inherently disadvantageous to some Filipinos could make their doctors similarly inaccessible for complaints. Or, if not exactly inaccessible, another futile channel.

So doctors need to establish channels of communication with patients that will allow the latter to feel direct approach possible. Yet if the communication between a patient and his doctor had been working properly from the start, there might not have been cause for complaint in the first place. Most patient complaints have to do with a mismatch between outcomes and expectations; the latter are strongly affected by communication.

Doctors may need to expend more effort in ensuring that their expectations and their patients’ are in line with each other. Even with only one objective—improvement of health and overall well-being—expectations of how much can be done, what can be done, and how it can be done may be very different.

It is misleading to think the solution simple. Even were this easily achieved, there would be no promises. Tension can remain in any case even after doctors and patients finally have the same answers to the critical questions.

Consider a study published in the New England Journal of Medicine. It found that most patients receiving chemotherapy for incurable cancers think the treatment curative. Even after doctors helped them understand it was only palliative, patient satisfaction with the physicians failed to improve (in fact, it degraded).

This is an extreme medical situation, though—perhaps anyone would feel dissatisfied with another who informs him that his condition is genuinely terminal.

It would be jumping the gun to give Filipino doctor-patient relationships a similar prognosis. There is much to be done, but if both sides realize the necessity of doing it together, that may facilitate the process. In a review of doctor-patient communication literature published in The Ochsner Journal, the authors observed that

[m]uch patient dissatisfaction and many complaints are due to breakdown in the doctor-patient relationship. […] Most complaints about doctors are related to issues of communication, not clinical competency. Patients want doctors who can skillfully diagnose and treat their sicknesses as well as communicate with them effectively.

The authors also noted that physicians unfortunately tend to overestimate their abilities in communication. (Of course, there is nothing to prevent supposition that some patients may do the same.)

Some doctors have already begun to take steps to handle their side of the issue when it pops up. Dr. Rolando Enrique Domingo of the UP College of Medicine held a recent webinar on the topic:

The webinar aimed to help doctors deal better with social media complaints.

Webinars like these are undeniably useful to doctors in this age. Yet the real challenge remains how to stop doctor-shaming social media complaints from coming their way. As they themselves like to say, prevention is better than a cure… so making patients feel that they have no need to doctor-shame comes first.

Ultimately, patients and doctors may need to re-learn how to communicate with each other. Social media can actually contribute positively to that. Many doctors in the country may feel wary of how colleagues have been shamed on it, but it can be as much a tool for as a weapon against them. As there is no reason to expect that social media shall either vanish or be curbed in the future, it would be wiser to make peace with it.

The question now is how to use this and other tools to establish a renewed doctor-patient relationship. It should be a collaborative one that no longer places patients and doctors at opposite sides of a distinct fence—whether it is a socioeconomic, educational, or even emotional barrier.

Love this post? Share it in your Facebook or social media feed and help us spread the word. Just click the icon over there on the left side of the screen to share.

Bravo on an eye opening and informative article. A few things: 1) As much as feedback is important for both sides to maintain a good relationship, I think that the public needs to know that they have to actually fill up the feedback form for it to work. It never fails to disappoint me how patients will take the 10 or so minutes to do a social media post but can’t get bothered to answer a survey on performance of the medical staff. 2) Which leads me to: simpler and easier ways to do feedback needs to be devised so that patients get to air their grievances. 3) Physicians also need to know and accept that feedback is not a way for patients to “get back at them” but rather a way for them to improve. It hurts sometimes but is important in the growth as a physician. 4) Patients shaming their physicians are also part of this phenomenon of people losing inhibitions because of relative anonymity and thus feeling “brave” about “outing” their physicians. Physicians are put in a position of power, through perception, and having them be wrong and most patients having no power to tell them of the mistake, turn to social media and resorting to what becomes a mob mentality. The bullied and the underdog become top dog.

Hi Doc Ribano!

Thanks for sharing your thoughts!

I totally get what you are saying. Doc Gia and I discussed this when we met last time and she mentioned practically the same things you did! 🙂

One of the things that we aim to do with SeriousMD is to improve the doctor-patient relationship. Can’t wait to roll out the things we’ve got in store.

Would love to hear what other docs think about this as well!

I’m sure there are many that do not prefer #2 and #3 in your list.